On a recent episode of Finding Our Way, Jesse and I spoke with Tim Kieschnick. I worked with Tim for about a year, and learned a ton from our collaboration. He’s an interesting cat—he worked at Kaiser Permanente for 30 years (until retirement), and in that time helped establish their web presence, UX as a practice, service design, and HCD/Design Thinking/Design Sprints. He’s a reflective practitioner, and through his experience developed two frameworks which I have in turn used in my thought partnership practice with design leaders. I was eager for him to share his wisdom on our podcast.

The 3Ps of the Leadership Ceiling

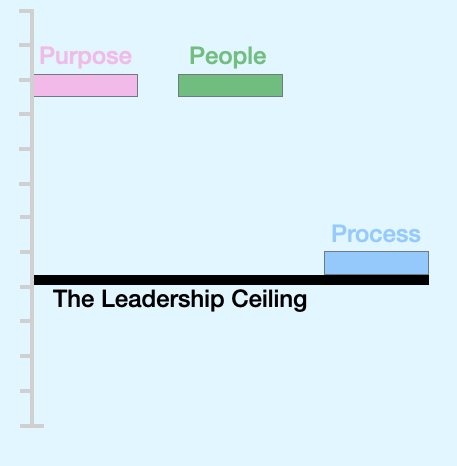

A little over a year ago, at my urging (so I could refer to it without feeling like I was plagiarizing), Tim posted an introduction to The Leadership Ceiling. (some of what I write here will repeat what’s over there, but in my words.) At heart, it’s a simple construct: Leaders create a conceptual ceiling above which their organization cannot rise. Tim identifies three ceilings:

Purpose

Why does this organization exist? How is that purpose articulated? Are we driving toward output, or outcomes? How does our purpose inspire, connecting people with their higher, better selves?

People

Who is in this organization? What is the caliber of contributor? And, are we creating a truly people-centered organization that enables those folks to deliver at their best?

Process

How is the work getting done? Does our process bog us down, or lift us up? How are we coordinating across functions? Are people spread too thin, across too many initiatives, or are they able to maintain focus and commitment? Are teams empowered to practice a process that is ‘fit for purpose,’ or is there an imposed standard way of doing things that cannot be deviated from?

(This is reminiscent of what Daniel Pink identified in Drive, in terms of what it takes to motivate people: provide them Autonomy (process), Mastery (people), and Purpose.)

In my experience, I don’t see three ceilings, rather one ceiling that is a product of how these three factors intersect. In my work with design leaders, looking at the intersection has proven helpful, because it illuminates why there’s cognitive dissonance between the message they’re getting from their leadership, and why the work doesn’t meet their expectations.

The diagram to the right shows my take on this aspect, which is that the Leadership Ceiling is set by which ever factor is lowest.

For instance, I’ve supported a number of banks and insurance services firms. And nearly all of them have high-minded aspirations for their business, with mission statements about empowering people’s financial wellbeing, or improving the health of all Americans. And these firms will also have committed to providing a much more conscientious work environment that encourages bringing your whole self, and stresses values of psychological safety and vulnerability.

But these large legacy organizations are bogged down in process, for reasons including bureaucracy, poor organization design, unwillingness to truly empower teams, people spread too thin across too many workstreams, etc.

And so, the Leadership Ceiling is established by that lowest factor. And the design leaders I work with, who may have been sold on a company’s vision and culture, then struggle when they realize that for all that high-and-mighty talk, their ability to deliver is severely hamstrung by a lack of attention to process.

The ABC’s of The Leadership Ceiling

Once you understand the height of a Leadership Ceiling, then you have to figure out your relationship to it. Tim uses an ABC mnemonic to think through what you can do:

You can try to work Above the ceiling

This approach is pretty common for designers, particularly new to an organization, who see their job as to ‘fix’ whatever came before, or to realize a bold new innovative vision. And they may see their leader’s Ceiling, and perhaps engaged in some effort where they bumped their head on the ceiling, and then see their job as the innovative iconoclast to work above the ceiling, to show to the rest of the org just how great it can be.

This never works. You might get some time to play in that rarefied air, but inevitably the leader’s Ceiling does its thing, often in the form of the Leader being frustrated that the designer isn’t doing what was expected of them, instead pursuing some quixotic endeavor that was bound to go nowhere.

So, most of us end up working Below the ceiling

We realize that we are constrained by the leader’s ceiling, and focus our efforts there. The dream is to have a leader with a high ceiling across all 3Ps, providing all kinds of headroom to innovate and grow. But most of us find ourselves below a ceiling lower than our liking, and so we have to make a choice:

We can Bail. We may believe that we’ll never reach our potential, or that work will be endlessly frustrating, and given our limited time on this planet, we want to focus our energies elsewhere. (This has been what I do. This model has helped me realize that I have little tolerance for working under a low, or even medium-height, ceiling.)

We can Bide our time. We make the best of the situation in front of us, delivering excellence within the leader’s constraints. Biding may sound defeatist, but it shouldn’t be perceived as settling. It can be a smart and pragmatic strategy of getting things ready for when the time comes and either our leader raises the ceiling, or is replaced by someone with a higher ceiling. In the podcast, we talked to Tim about telehealth, which Kaiser Permanente had been pursuing for 25 years. And if you were passionate about telehealth, you were likely frustrated, because it never caught on the way you felt it should—the organization wouldn’t invest in it and the membership didn’t seem to appreciate the convenience.

And then 2020 happens, the world goes on lockdown, and that causes the Ceiling to be raised on telehealth. And all those folks who had been biding their time, waiting for the moment, are now center-stage.

Some bold souls may seek to Change the ceiling

As Tim puts it, this “is not for the faint of heart.” But if you are frustrated by the height of the ceiling, and you’re not content working Below it, and you’re committed to the organizational cause and so you won’t just Bail, you can try to change the ceiling. This requires diagnosing just what is depressing the ceiling, developing an argument and a plan for raising the ceiling, and then doing the hard work of education and evangelism to persuade leaders to change the ceiling. This is particularly tricky, because those leaders, over their career, have received a lot of confirming feedback about the rightness of their decisions, and now someone within their org is going to tell them that they’ve got it wrong? So, it requires delicate, incisive, and persistent communication to figure out what stories resonate with the leader and encourage them to evolve their view.

I’m so grateful Tim spoke with us, and driving broader awareness of this framework. I’ve found it quite useful in my work helping design leaders succeed, and I’d love to hear (or read) how it works for you.

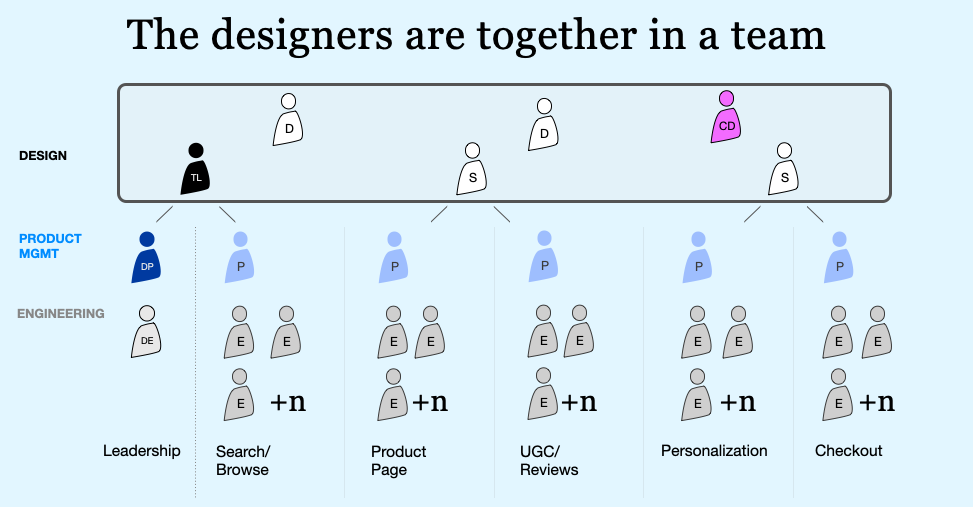

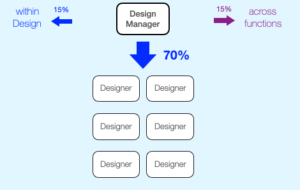

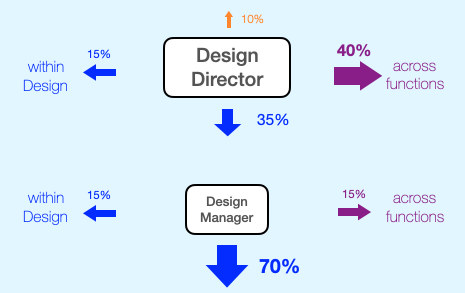

Their primary orientation is downward. They’re focused on getting the most out of the team the manage, making sure they’re delivering on expectations in terms of addressing problems and upholding quality.

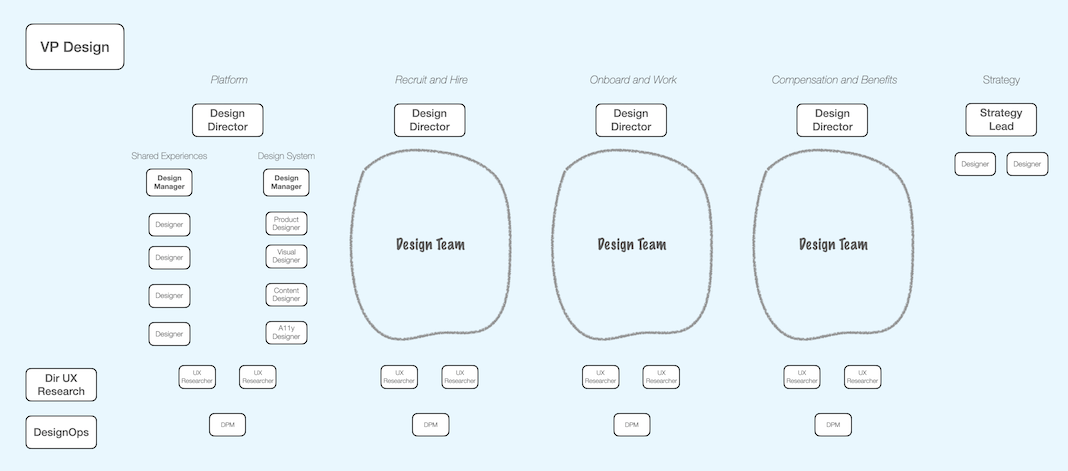

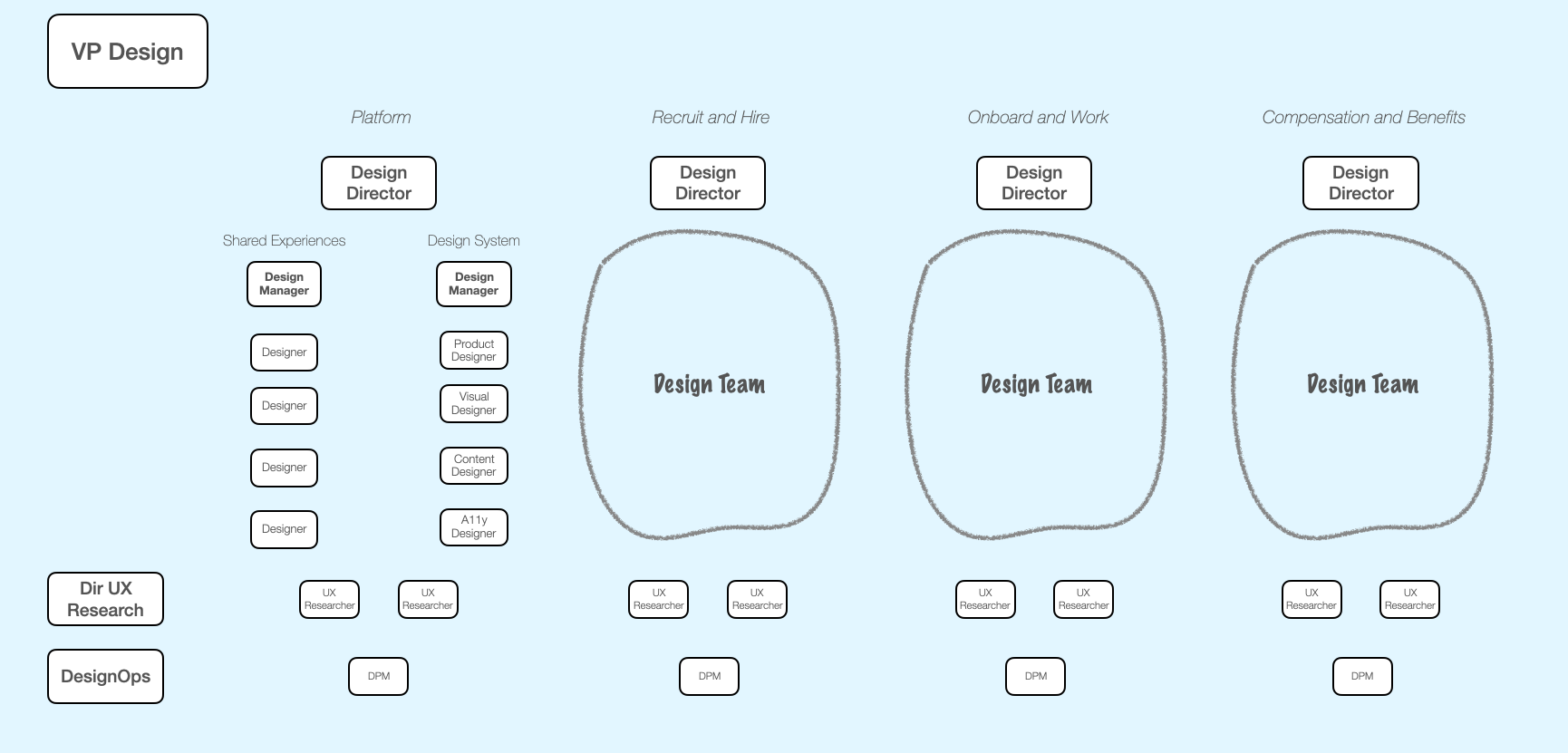

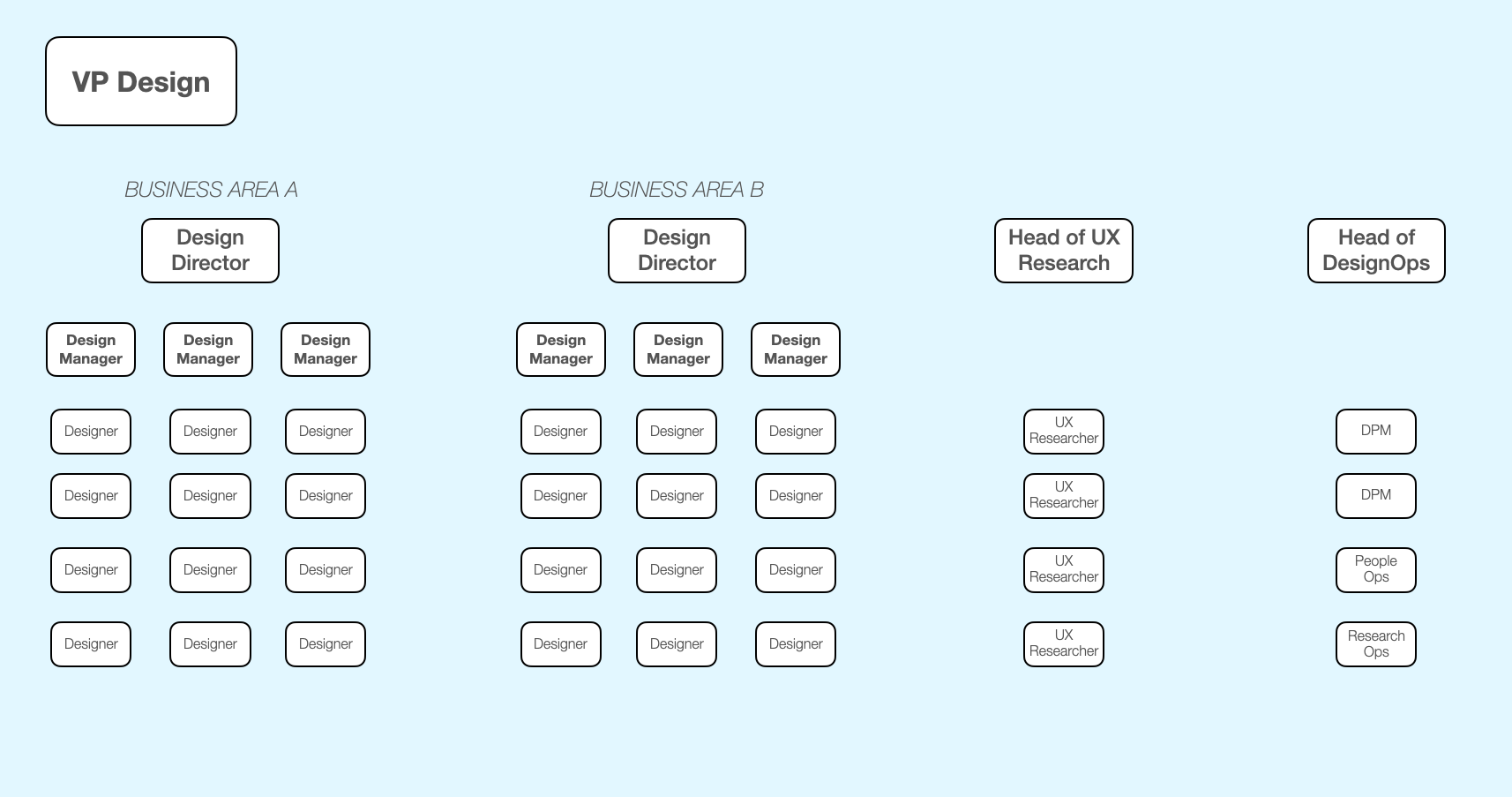

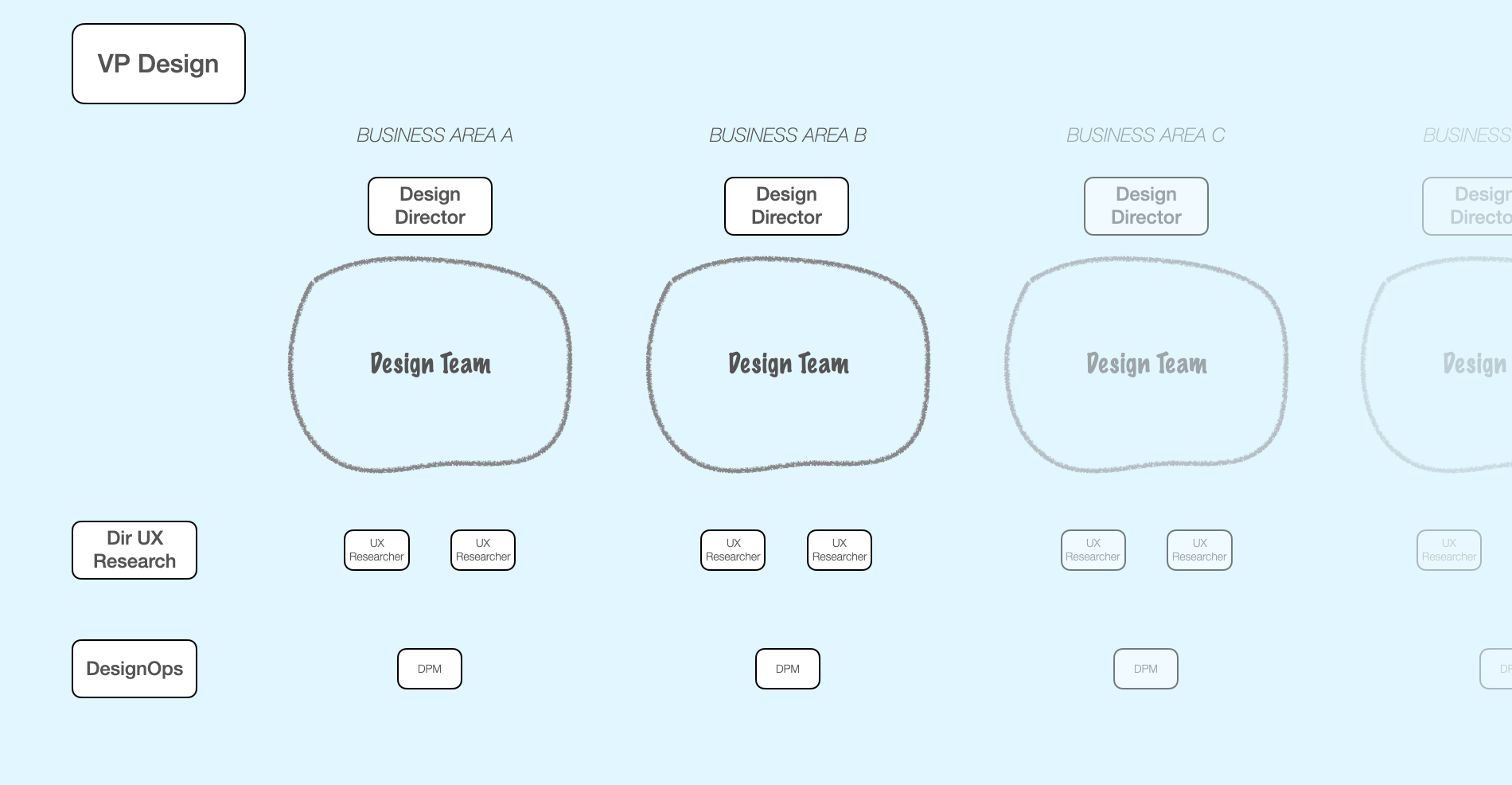

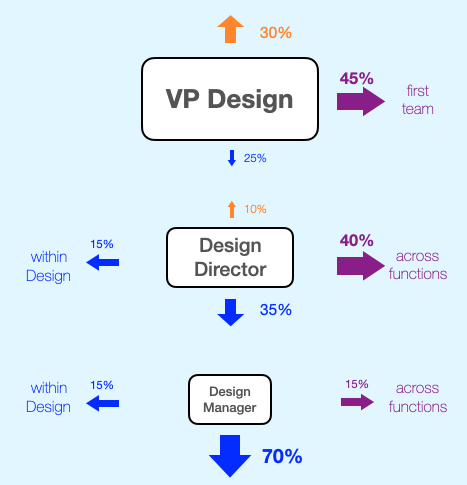

Their primary orientation is downward. They’re focused on getting the most out of the team the manage, making sure they’re delivering on expectations in terms of addressing problems and upholding quality. A Design Director’s primary orientation is sideways, and not only that it’s mostly outside of Design. An effective Design Director should be spending more of their time and energy working with non-design peers and other stakeholders than with any other kind of colleague.

A Design Director’s primary orientation is sideways, and not only that it’s mostly outside of Design. An effective Design Director should be spending more of their time and energy working with non-design peers and other stakeholders than with any other kind of colleague. And in terms of time spent, it goes even farther than that. The Design Team should be where a Design Executive spends the least amount of time. Their primary orientation is sideways, toward their executive peers. This is about planning and strategy for the organization, identifying opportunities for the business and how their coordinated teams can realize them.

And in terms of time spent, it goes even farther than that. The Design Team should be where a Design Executive spends the least amount of time. Their primary orientation is sideways, toward their executive peers. This is about planning and strategy for the organization, identifying opportunities for the business and how their coordinated teams can realize them.