I am a beneficiary of career practices (particularly within the field of UX/Design) that provided junior folks opportunities to work. I started as an intern at a multimedia CD-ROM company. Then I worked at a design firm that actively encouraged my professional growth as I shifted from early web development into interaction design.

Later in my career, when I was in a position of authority, I helped institute internship programs, and eagerly sought young talent emerging from schools. I fought for professional development budgets so team members could grow their skills through courses, and meet their peers at conferences.

Last week, I was the guest of a UX course at UC Berkeley's iSchool, taking part in an extensive Q&A. Through the discussion, I realized how the current generation of UX/Design leaders have abandoned their obligation to the next generation of UX professionals.

Figma's "The demand for design hiring in 2026" report

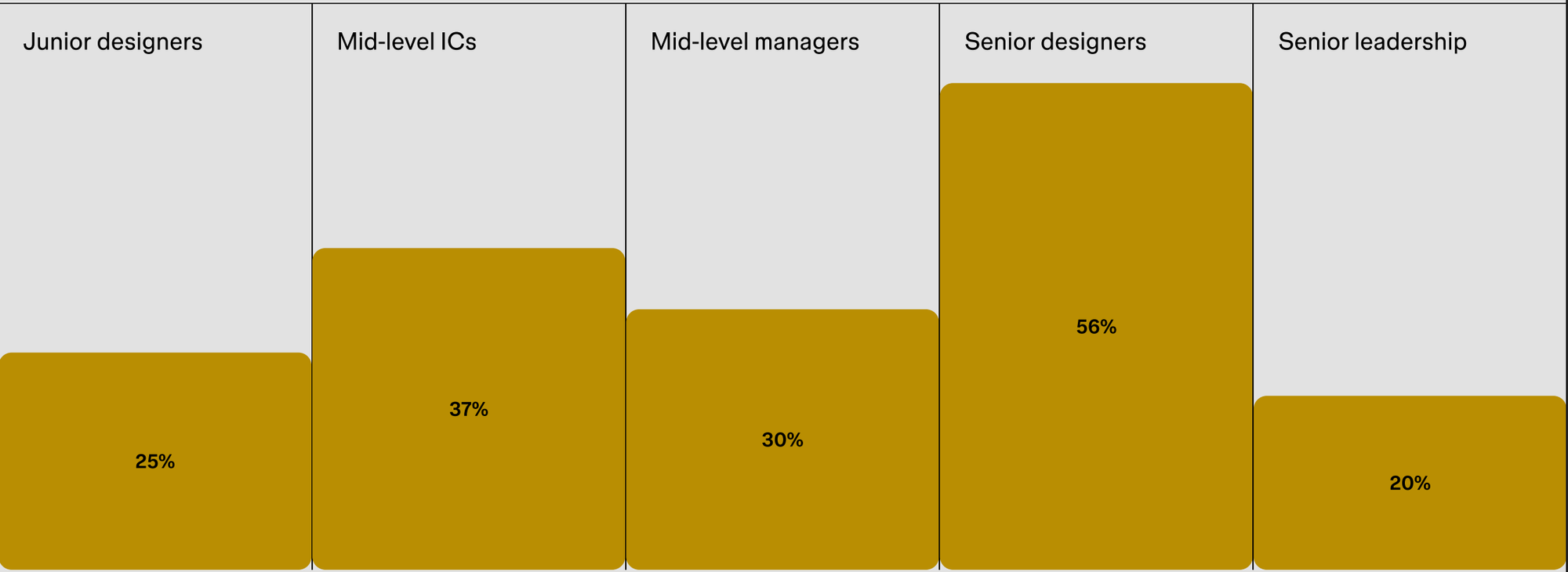

Coincidentally, last week was when Figma dropped their "The demand for design hiring in 2026" report. Within it is the tragic finding that UX/Design hiring managers prioritize hiring senior designers more than double than hiring junior designers.

The accompanying blog post highlights how managers are seeking to hire designers already with some familiarity with the challenges the companies are facing, including leveraging AI. The conversations I've had with design leaders suggest that many companies think they may be able to simply replace junior designers with AI tools.

Managers who cannot be bothered

But, it's worth pointing out that this issue does not begin with "AI." I first saw this about 15 years ago, when I shifted from working at Adaptive Path to being an in-house design executive. I was charged with growing my org, and tasked the directors and managers in my team to begin hiring. I noticed that one Director only opened reqs for Senior Designers. When I asked them about it, they said, "I don't have time to manage people. So I need folks who don't need to be managed."

I have had some variation of this discussion throughout my work (either as an executive or org consultant) since then. And while I understand that many of these folks are overly tasked, their apathy towards getting this situation right upsets me.

Frankly, I saw a bunch of leaders who, I think, simply didn't want to manage people, didn't want to put the effort into developing the next generation, and found an excuse not to.

The insipidity of "agile" practices

Manager overwhelm and/or apathy doesn't explain it all, though. Four years ago, I wrote "'Agile' is eating design's young; or, Yet Another Reason why 'embedding' designers doesn't work," unpacking how the common practice of embedding a single designer within a product team means that companies prefer Senior Designers who can hold their own in such situations, and leaves no room for entry-level designers.

Underinvestment in professional development

Though, even when organizations do hire junior talent, they're not setting them up for success. Among the clearest findings in the 2025 State of UX/Design Organizational Health research is that professional development is not a priority for these organizations. Two statements addressed this directly, and responses to this were among the lowest scores in the whole project:

A couple weeks ago, I wrote about how this may be contributing to the plight of Senior UX/Design practitioners. It's likely an even bigger issue for people right at the outset of their careers.

Now, some leaders may say, "I'm not given an L&D [learning and development] budget, what am I supposed to do?" but that's a cop out. If you're not given a budget, what steps are you taking to constructively champion for learning and development resources? If you can't get resources, what are you doing to develop internal mentorship programs?

And something you don't need budget for is something too often overlooked: clear career architectures. There's no excuse to not provide the people in your organization an understanding of what's expected of them as they advance in their career.

The lack of community and professional associations

In the iSchool class, a student asked where she could find a community of people that she could grow with. As I stumbled to answer the question, it dawned on me just how little institutional support there is for professionals in UX/Design, a circumstance that is most damaging to those earliest in their careers.

The Interaction Design Association (IxDA) shuttered; the IA Institute (IAI) couldn't manage; SIGCHI is too academic; HFES is narrowly specialized; UXPA is not particularly reputable; AIGA has struggled growing past its graphic design core. The best we could come up with are EPIC (which is primarily focused on UX research and applied social science) and the Service Design Network (SDN), which remains uncertain about its relationship to digital product design.

Upon reflection, this lack of institutional professional support for the most commonly practiced kind of design is stunning and appalling. That no credible organization has emerged to serve digital product designers—despite the field's explosive growth over three decades into the predominant design discipline—represents a failure of our industry's leadership.

In the early 2000's, responding to a recognized need to establish legitimacy and connection, a burst of energy lead to the IxDA and IAI. Now, our field's most prominent voices and celebrated leaders seemingly can't be bothered to build the infrastructure that every mature profession requires, perhaps because we personally don't need it any more. This has abandoned the next generation, who could benefit from the connection and professional framework, and are instead left to navigate Slack, Discord, and Meetup communities in hope of finding people in shared circumstance to go on this journey together.

(Putting my money where my mouth is: if there are folks truly and seriously interested in addressing this professional association gap, ping me.)

The decline of the design agency and the shift to in-house

OK. So, this one is not a leadership failure, but something I think still worth calling out as we consider the challenges of entry-level folks getting a foothold in our profession.

A force that must be considered is the decline of the design agency, and the shift to in-house staffing. The lifeblood of design agencies is earlier-career talent. The economics of services firms encourages a few senior principals and scads of junior professionals. And design firms drew from a kind of master-apprentice legacy, with the mentorship that implies, and also had a mature understanding of career development (I still remember the Junior Designer–Designer–Senior Designer–Art Director–Creative Director–Executive Creative Director path from the one typical agency I worked at).

In the mid-to-late-aughts, the shift to in-house UX/Design was well underway, and by 2020 it seemed as if only 5-10% of UX/Design practitioners worked in a consulting capacity.

And while in-house designers generally got paid more, what they gave up was an ability to truly focus on developing their practice. Agencies were environments dedicated to delivering the highest quality design—that was their whole reason for being. In-house, UX/Design orgs are part of a machine of product development, embedded in a different understanding of value and values.

As noted earlier, that machine is often performing a sad excuse for 'agile,' leading to designers working in isolation. In an agency environment, designers never work alone, because the best design work comes from collaboration with other designers.

In-house, the "typical" 1:8 designer:engineer ratio comes with the implication that engineers are working in teams, and those teams most certainly have capacity for a range of professional experience. I've come to believe that much that is wrong about how design operates inside organizations is because it does so in reaction to what's considered best for engineers, instead of what's best for the function of UX/Design.

The health of our practice depends on this

These students at Berkeley are inheriting a field where managers won't manage, organizations won't train, and a practice so scattered that it cannot support a professional association for the hundreds of thousands of people doing this work.

All of which indicates that industry leaders decided that developing the next generation was optional. Which strikes me as quite selfish and self-centered—we had to make it up as we went along, so why shouldn't they?

But this isn't sustainable. A practice that won't enable its junior adherents will wither. And before that, it risks becomes irrelevant—the perspectives of new generations, and their challenges to orthodoxy, are what keep any practice fresh.

![[TMA] UX/Design Leaders Are Failing the Next Generations](/content/images/size/w2400/2026/02/ChatGPT-Image-Feb-17--2026--06_17_15-AM.png)