Blog

OKRs for Design Orgs

· Peter Merholz

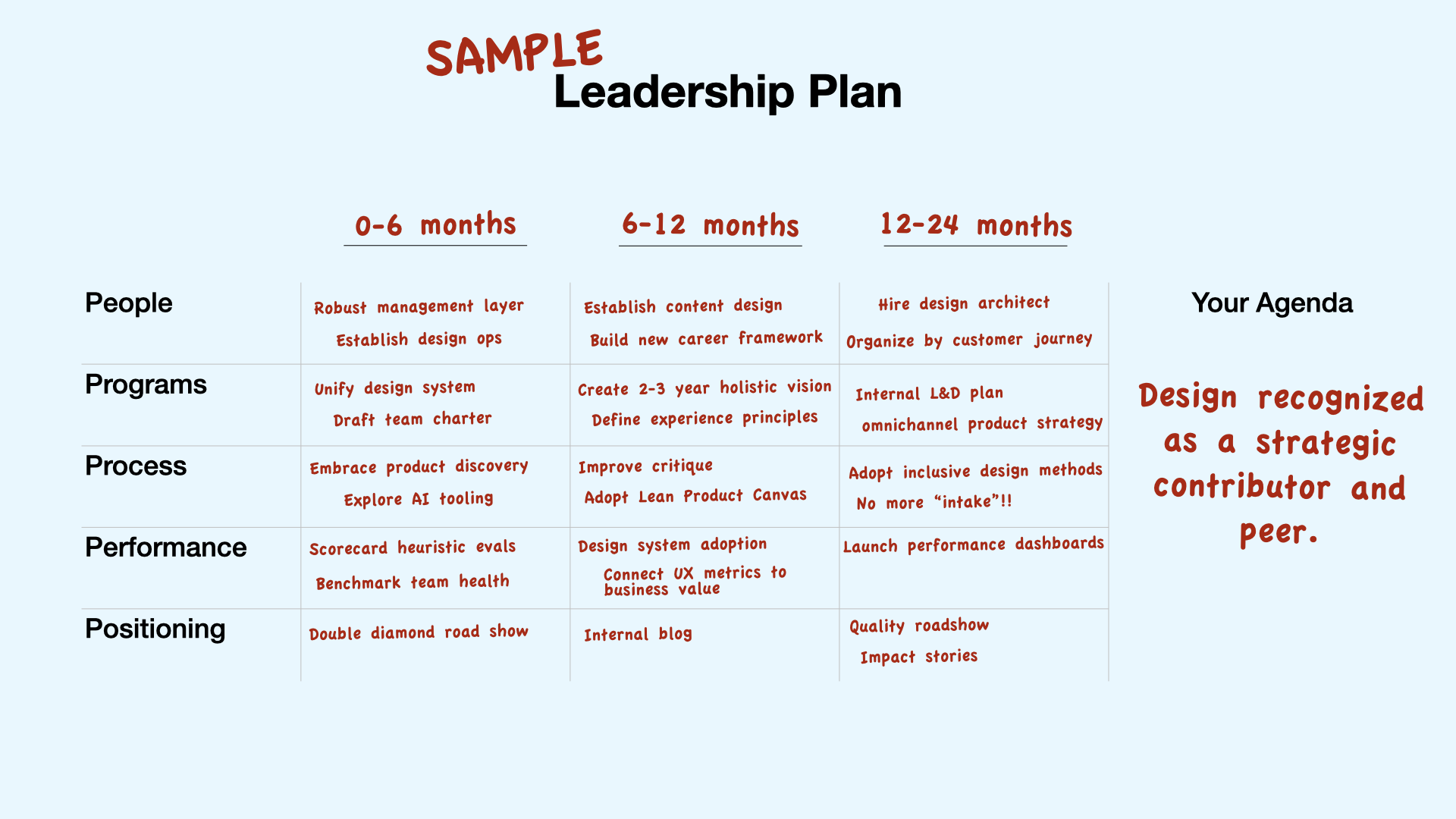

Craft Your Leadership Plan with These 5 P's

· Peter Merholz

Critique is not review, and many other thoughts on an overlooked practice

· Peter Merholz

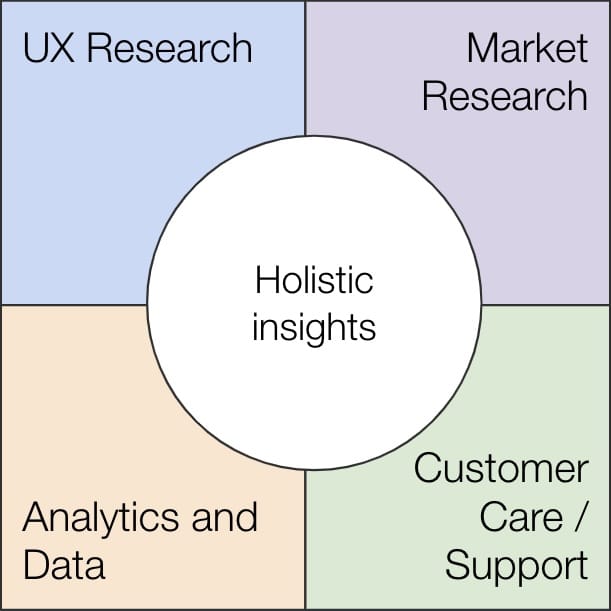

Whither UX Research?

· Peter Merholz

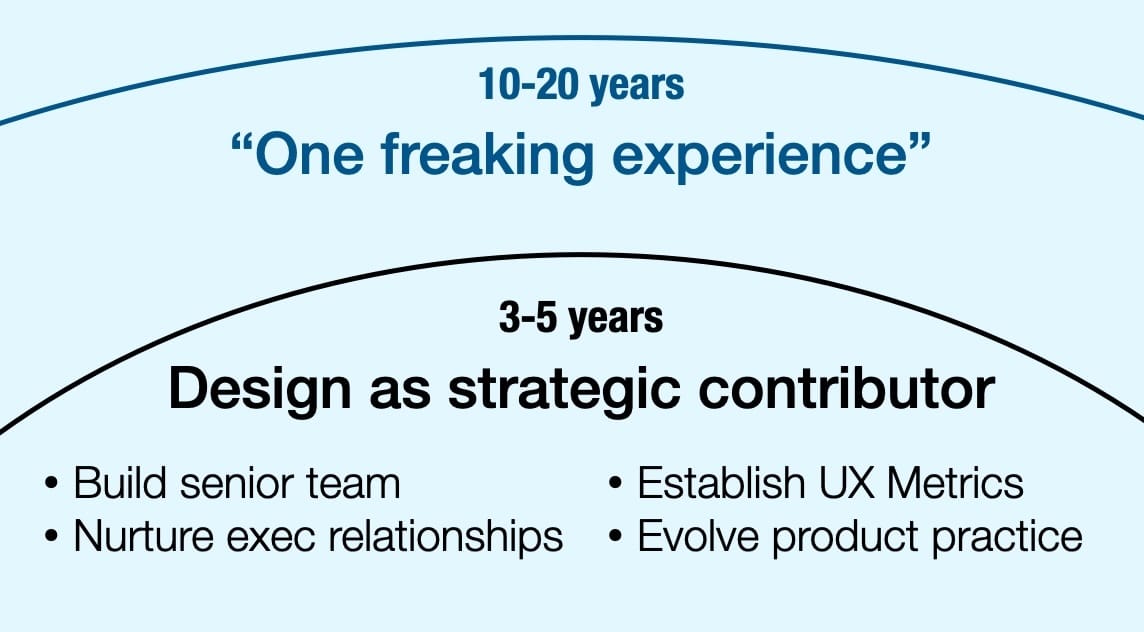

To Lead Design, You Must Have an Agenda

· Peter Merholz

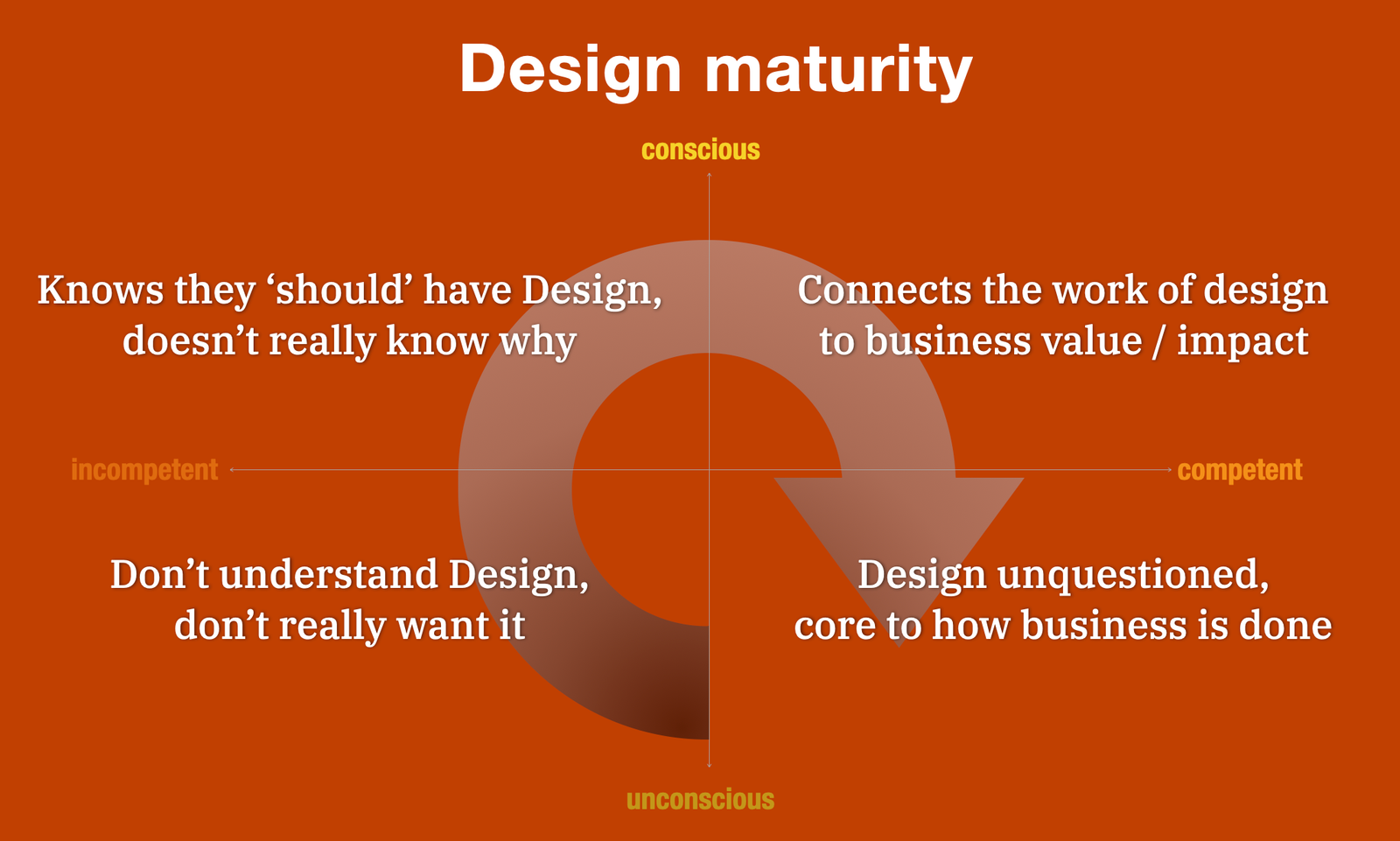

On the (f)utility of design maturity models

· Peter Merholz

UX/Design Leaders: Understand the motivation of your peers and stakeholders the same way you do your users and customers

· Peter Merholz

New masterclass: "From Ladder to Trellis: Flexible Career Architectures for UX Teams"

· Peter Merholz

Metrics and UX/Design Maturity

· Peter Merholz

Design leadership is change management

· Peter Merholz

Org Design for Brand Design Orgs

· Peter Merholz

The 'management carousel' inhibits UX professional growth

· Peter Merholz

The Leadership Ceiling: a framework for diagnosing your situation

· Peter Merholz

"Agile" is eating design's young; or, Yet Another Reason why "embedding" designers doesn't work

· Peter Merholz

Design orgs are their own greatest impediment to success in recruiting and hiring

· Peter Merholz

From the Weeds to the Board Room—How Design Leaders shift from managing down to up and out

When working with executive design leaders across organizations, I often hear something along these lines. Their Managers and Directors don't know how to best spend their time, and where to focus their attention.

· Peter Merholz

Creative and Strategic Leadership in Design Orgs—Super-Senior ICs and the Shadow Strategy Team (3rd in a series on Emerging Shape of Design Orgs)

· Peter Merholz

Design Systems and Structural Integrity—Emerging Shape of Design Orgs (2nd in a series)

· Peter Merholz

The Emerging Shape of Design Orgs (first in a series of I don't know how many)

· Peter Merholz

This interview with Billie Jean King is a masterclass on leadership

· Peter Merholz

It was 20 years ago today...

· Peter Merholz

Waking up from the dream of UX

· Peter Merholz

The Craft(s) of Leadership: Communication and Information Architecture

· Peter Merholz

Firing is often not an act of accountability, but cowardice

· Peter Merholz

The cultural divides within product and marketing teams

· Peter Merholz

What is "good design," anyway?—it's crucial for design orgs to define quality

· Peter Merholz

End of the work year reflections on design, design leadership, and org design for design orgs

· Peter Merholz

The most difficult thing for a Design Executive to accept...

· Peter Merholz

The Makeup of a Design Leadership Team

· Peter Merholz

The Makeup of a Design Executive (Chief Design Officer, S/VP of Design)

· Peter Merholz