A few years ago, we interviewed Jen Cardello for Finding Our Way, and she shared that her team (UX Research) is peered with “market research, behavioral economics, brand, and advertising research, and customer loyalty” in an independent Insights team. The idea was for research to avoid a functional bias, so that it couldn’t be “weaponized” by marketing or design.

And while UX Research is still typically found within a UX/Design organization, I’m witnessing a nascent trend of it being located elsewhere. For example, Nalini Kotamraju, SVP of Research and Insights at Salesforce, shared in a discussion on making research leadership more effective, that her team has “moved out of UX,” to be part of a broader product function.

At the heart of this is a recognition that siloed research leads to a fractured understanding of the people the business is serving and territoriality around the idea of ‘who owns the customer,’ and that to be its most effective, research needs to engage in the entire end-to-end service experience, and that journey spans many organizational functions.

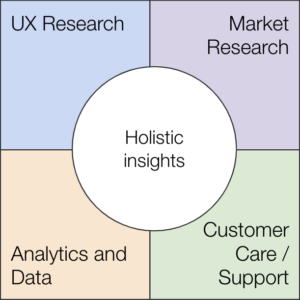

And in my work, I’ve started recommending to my clients that they consider the creation of these holistic insights teams, using the simple diagram at the right to show how what are typically seen as distinct practices are actually puzzle pieces fitting together as a whole.

Proceed with some caution

While an independent, holistic, and robust Insights org is the best mechanism for rich customer and user understanding, there are preconditions required in order for it to succeed.

A move towards an integrated Insights organization will likely be a journey, and must be taken with care. What’s crucial is that for the ‘containing’ function for UX Research to be a strong advocate and capable steward. If UX Research is moved out of UX/Design and into Marketing (to be partnered with Market Research), that could prove detrimental if Marketing leadership favors quantitative insights, or doesn’t understand the value of generative methods. In such a case, it would be better for UX Research to remain in UX/Design, where, even if its purview is limited, it can engage in a fuller practice.

Perhaps the greatest risk for a separate Insights group is to be seen as a disconnected internal consultant, dismissable by folks in Marketing or Product who feel that Insights isn’t aware of the real challenges on the ground, or simply ostracized because of some internal “us vs them” mentality. (I’ve talked about this as a challenge for strategic design.)

So, in order for this to work, your company must be a true ‘learning organization.’ In our discussion, Jen shared that Fidelity “is so obsessed with learning. We actually have learning days. Every Tuesday is a learning day.” Instead of worrying about being ignored or neglected, Insights has the opposite (and good) problem of being in too much demand.

Another factor for any organization design is professional development. The ‘containing’ organization needs to be one that those practitioners aspire to lead. When UX Research is embedded within UX/Design, that implies that the career path for those UX Researchers is to become UX/Design Leaders. Is that true? Or are they better suited to becoming “Insights” or “Strategy” leaders? (The same holds for other functions like Accessibility. While many Accessibility teams start within UX/Design, those Accessibility practitioners typically don’t see their career heading toward UX/Design leadership, which suggests they belong somewhere else in the organization).

How is your Research org organized?

9 years ago, we started the process of writing Org Design for Design Orgs because there was burgeoning demand for making sense of the UX/Design function within companies. It now feels as if (UX/Market/Etc.) Research is in a similar moment. Who’s writing Org Design for Research Orgs?