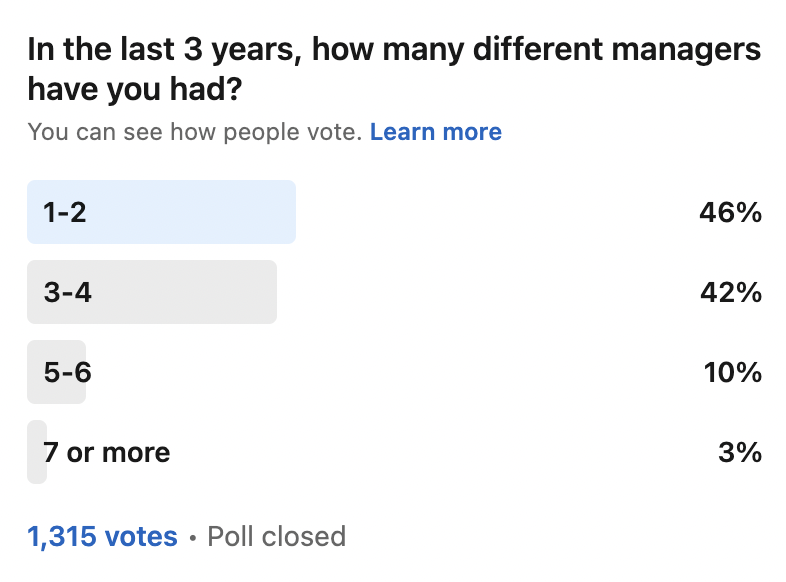

Every design manager knows there’s an intense war for talent. It’s been going on for the past 15 years, and has definitely ratcheted up in the past 12-18 months.

Last year, I supported one team that grew from 14 in March to over 40 by the end of the year. This wasn’t some sexy tech company—it was enterprise SaaS supporting HR. I point this out because, even in with all the competition, it’s quite possible to scale an organization. The issue, which I’ve seen over and over again for years, is that most design orgs are just bad at recruiting and hiring, getting in their own ways. Here are the top mistakes that I’ve seen.

Hiring Managers don’t devote the necessary time

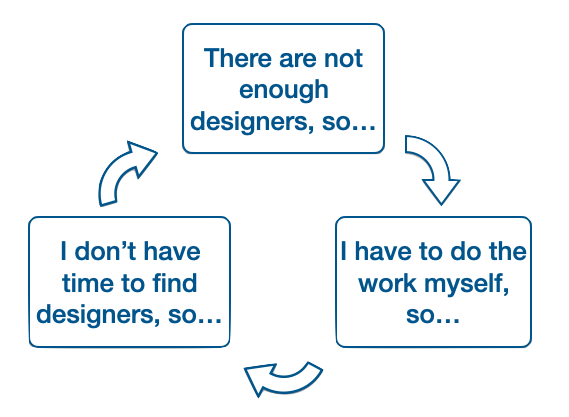

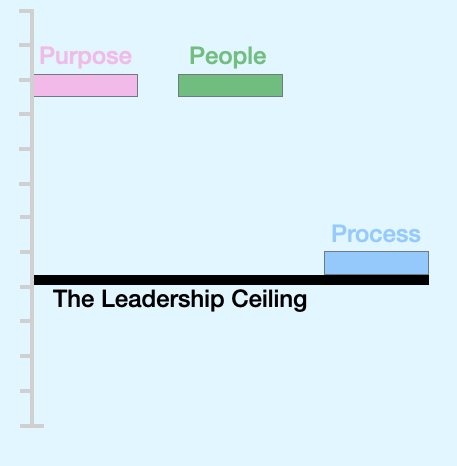

Hiring Managers are busy people. Their attention is pulled in many directions. They are expected to lead their team, provide creative vision, manage the individuals, partner with cross-functional peers, roll up their sleeves and do the work, oh, yeah, and build their team. That last item gets deferred, as it doesn’t have the urgency of their other responsibilities. As such, many Hiring Managers find themselves in this cycle:

Perhaps the single most impactful thing a Hiring Manager can do is protect their time for recruiting and hiring. When active, expect to spend about 4 hours per week per open headcount—this accounts for time spent sourcing, reaching out to prospective candidates, initial conversations to gauge interest, deeper conversations once someone applies, and the background stuff around planning and preparing others to support the hiring process.

Over-reliance on Recruiters

When I counsel design executives and their leadership teams about recruiting and hiring practices, I often get a variant of the reply, “Isn’t that the Recruiter’s job?” The short answer is: No.

This isn’t to say you shouldn’t develop a strong partnership with your Recruiting team. But, I’ve seen, again and again, that when Design Leaders rely on a separate Recruiting team, particularly for sourcing potential candidates, their efforts come up short.

The Design Org needs to own their recruiting and hiring practices and processes. The Recruiting partners are their to support you, not do your job for you.

Under-reliance on the rest of the Design org

While Hiring Managers need to be the engine that drives recruiting and hiring, this doesn’t mean they operate as lone wolves, expected to do everything on their own. Hiring Managers must rely on support from others in the Design organization, specifically:

- Their manager — to help them protect their time, and manage the relationships with peers who may be upset that the Hiring Manager is focused on recruiting, and not “the work.”

- Their team — Hiring Managers should engage their team members in sourcing, gauging interest, and interviewing. Not only is this an example of “many hands make light work” (ok, lighter work), I have found that passive candidates (i.e., those not actively looking to change jobs) are often more receptive to outreach from another designer, in a way that they are not from a Design Manager, and definitely not from a Recruiter.

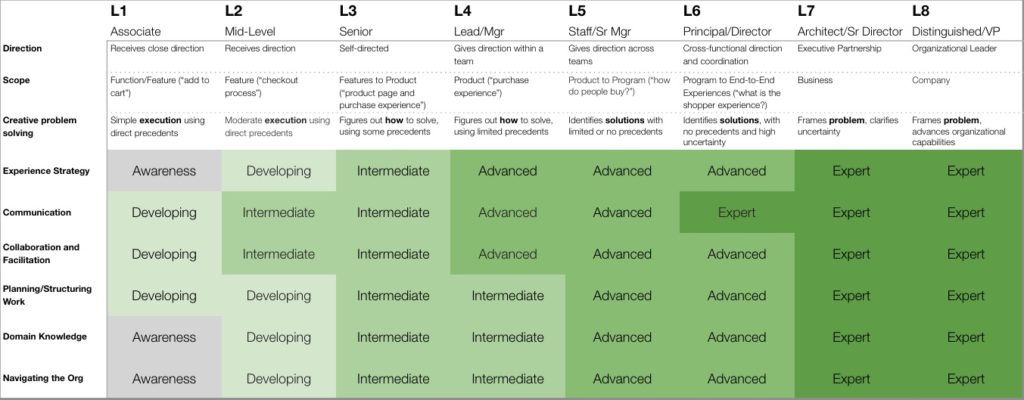

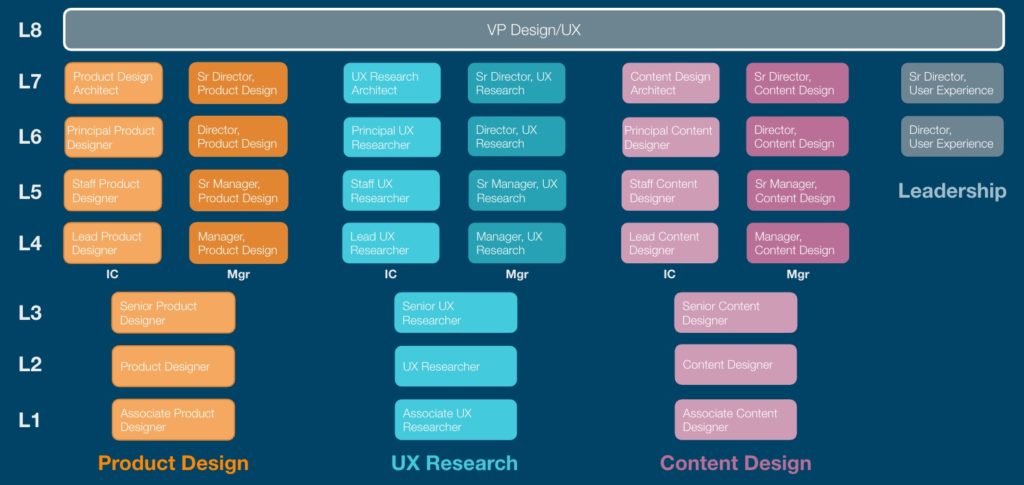

- Design Operations — Any scaling organization should have a “PeopleOps” person specific for Design, and among their responsibilities is maintaining a set of robust tools to support the recruiting process: job descriptions, career and levels frameworks, question banks, and assessment rubrics.

Insufficient articulation of the role(s) to be hired

Hiring Managers know they need people, and often take an existing job description, lightly revise it, and post it. They rarely do the diligence to figure out what they actually need in the role. This hinders the recruiting process, as it becomes apparent, through conversations with candidates and colleagues, that there is not a shared understanding of the profile we seek to hire.

This is a classic example of “measure twice, cut once.” A little more work upfront will lead to far less time spent down the line.

One tool I’ve begun to see great promise in is the Thank You Note, as posited by Jared Spool. This is an “artifact from the future,” where the Hiring Manager drafts a memo thanking the person for what they’ve accomplished in their first year. Putting yourself in that ‘year ahead’ mindset, while forcing yourself to be specific, results in essentially drafting the job description.

Cavalier recruiting processes that ignore known best practices

This frustrates me more than any other aspect, because solid practices for recruiting are not mysteries, but teams neglect them. Hiring Managers resort to what they’ve done in the past, and everyone wonders why it’s so hard to find good people.

Processes that are too lengthy or too brief

For a client I supported in 2016, I recommended shortening the interview day (which takes place after initial phone screens) to “5 hours, 6 hours most.” When I recently re-read that, had I been sipping a beverage, I would have done a spit-take. Because while that amount of time is too long, I’m now seeing teams that spend 2 hours with a candidate, total, before making a hiring decision, driven by the need to ‘act fast’ in this competitive market.

In my experience, there’s a “Goldilocks” scenario that works for most design/research/content hires:

- Two 30-45 minute phone screens, one conducted by the hiring manager to get a sense of the candidate as a professional, another by a team member digging in to the specifics of their craft

- Panel Presentation + four 1:1s, taking about 2.5-3.5 hours

You need to spend enough time to feel confident in the ‘signal’ you’re getting. But too much time leads to diminishing returns.

Adversarial stances with candidates

Many hiring managers (and their broader recruiting context) approach engaging candidates in an adversarial way, where the candidate has to ‘prove themselves’ worthy of consideration. Fuck that masculine posturing bullshit. Your company isn’t so great that it can act as if they’re deigning to speak with someone.

I’ve also heard Hiring Managers say that they don’t want to provide too much information (see the next item), because they felt part of the process was the candidate to figure out what’s expected. Recruiting processes shouldn’t be the conversational equivalent of an escape room, where the candidate solves the puzzle of ‘how do I get hired?”

And, for my sake, just stop with the design exercises. No, really.

No preparation for candidates or interview panelists

Perhaps because of the time constraints mentioned at the outset, I often find Hiring Managers (and Recruiters) do almost nothing to prepare either the candidates or the interview panelists about the process and what’s expected of them.

With candidates, sometimes it’s a matter of the prior point on adversarial stances, but often it’s just thoughtlessness. Apart from blocking time on their calendar, candidates often have no idea what to expect from conversation to conversation.

With panelists, often, they learn about an interview when a slot is dropped on their calendar, with no context, not even a resume or LinkedIn profile.

Candidates should be provided extensive preparation for the process. How long it will take; what the steps are; how to shape their portfolio presentation; whom they will be meeting and what topics will be addressed. We want to best know the candidate, and that means enabling them to present their best self.

Panelists should be coordinated such that each has a topic area that they dig into, and a set of questions to draw from. This avoids needless duplication across 1:1 interviews, and ensures a broader understanding of the candidate.

Gut-level judgment of candidates

Throughout the process, the assessments of candidates are typically superficial and gut-driven. Hiring Managers and panelists may take notes, but often there’s no standard by which to make a judgment, and so hiring decisions are based solely on feeling, rather than a considered judgment, placed against a robust profile of the role.

This gets back to the issue shared earlier, where Hiring Managers insufficiently articulate the profile of a desired candidate, so people don’t have a clear frame of reference for their judgment. This can lead to a couple of different problematic outcomes:

- the endless searching for some kind of unicorn who satisfies everyone

- offers extended to a candidate that everyone likes, but is actually not suited to the role: for example, hiring someone as a Lead Designer because everyone thinks highly of their design skills, but not enough was done to assess their leadership characteristics

A lack of up-front clarity also contributes to implicit bias, favoring candidates who ‘look the part,’ whether or not they’re best suited.

Assessment rubrics for each stage of the process should be clearly defined ahead of time. I’ve published a tool I’ve used to support portfolio reviews. You’ll need to come up with your own for other stages.

With solid assessment rubrics, hiring decisions become much clearer and with reduced bias. You know when someone is qualified, and you’re confident in making an offer.

And there’s more…

What’s shared here are the top mistakes that, in my view, contribute the most to poor recruiting outcomes. But by no means are they the only issues that commonly arise. Others include:

- Poorly written job descriptions, typically too vague, boilerplate, and littered with non-inclusive language that discourages qualified applicants

- Unclear or undefined levels framework, so judgments about job requirements, and then candidate aptitude, are made without any frame of reference

- Sourcing practices that don’t go beyond posting a job to a LinkedIn profile and hoping for the best

- Waiting too long to address the compensation conversation, only to find out in the offer stage that your salary band doesn’t meet candidate expectations

- Lack of appreciation for reference checks, the only tool in this process that engages people who have actually worked with the candidate

If this sounds like a lot, that’s because it is

Generally, design orgs simply have not treated recruiting and hiring with the focus, attention, planning, and effort that it deserves. It is somehow just expected to get done.

I find the story I told at the beginning, of a team going from 14 to 40 in a year, to be illustrative of a path forward. I was supporting that team, and probably spending ~10-15 hours a week on various activities that support recruiting (career ladders, job descriptions, working with recruiters, sourcing, interviews, etc.) By having a senior person in a People Ops-like role, who wasn’t weighed down with explicit management responsibility, who could develop materials to support recruiting practices, and also drive the effort in hiring key leadership roles, this team was able to scale quickly and with quality. Most teams aren’t willing to make such an up-front investment, instead hopeful that they can get by with what they have. What I’ve seen, though, is that orgs that make that investment, realize a worthwhile return.

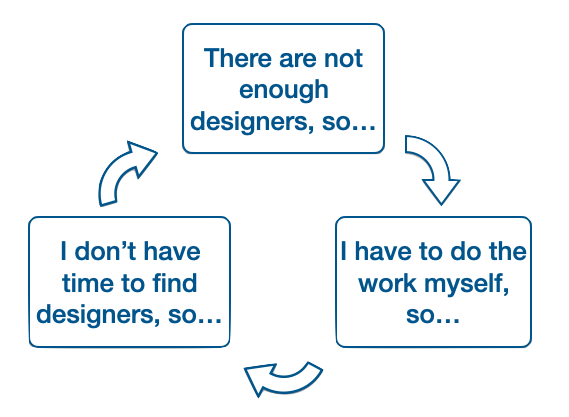

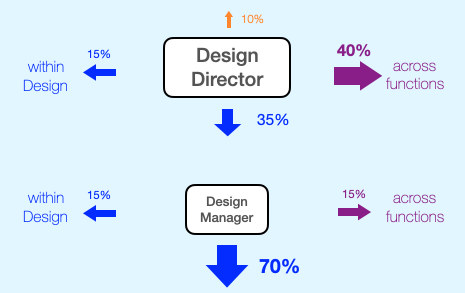

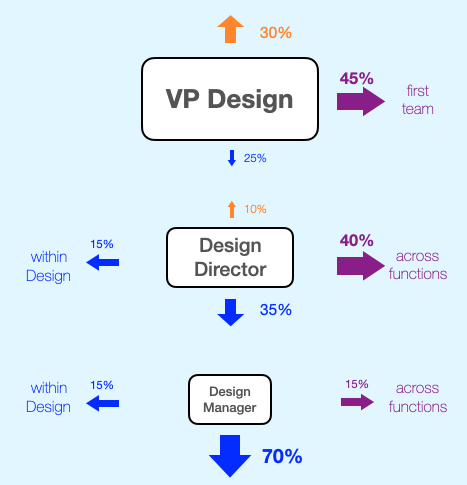

Their primary orientation is downward. They’re focused on getting the most out of the team the manage, making sure they’re delivering on expectations in terms of addressing problems and upholding quality.

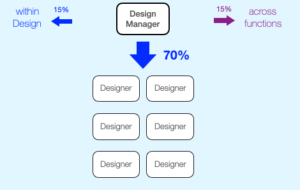

Their primary orientation is downward. They’re focused on getting the most out of the team the manage, making sure they’re delivering on expectations in terms of addressing problems and upholding quality. A Design Director’s primary orientation is sideways, and not only that it’s mostly outside of Design. An effective Design Director should be spending more of their time and energy working with non-design peers and other stakeholders than with any other kind of colleague.

A Design Director’s primary orientation is sideways, and not only that it’s mostly outside of Design. An effective Design Director should be spending more of their time and energy working with non-design peers and other stakeholders than with any other kind of colleague. And in terms of time spent, it goes even farther than that. The Design Team should be where a Design Executive spends the least amount of time. Their primary orientation is sideways, toward their executive peers. This is about planning and strategy for the organization, identifying opportunities for the business and how their coordinated teams can realize them.

And in terms of time spent, it goes even farther than that. The Design Team should be where a Design Executive spends the least amount of time. Their primary orientation is sideways, toward their executive peers. This is about planning and strategy for the organization, identifying opportunities for the business and how their coordinated teams can realize them.